Written by/Zou Ming Yi

Photographer/Zhuang Zhen Feng

Photos provided by the Pan Wei Li, Chen Nai Cheng, Li Yi Lun, Shutterstock

In an era of rapidly evolving AI and digital technology, children are no longer just “looking” at books with their eyes—they are learning to think, explore, and express. In the face of an information saturated environment, reading is no longer merely about decoding text; it has become a foundational skill for understanding the world, discerning truth from falsehood, and creating content. To equip the new generation with these essential competencies, schools across Taiwan are launching innovative initiatives that integrate reading promotion with AI technology, information literacy, and media literacy education ushering in a new chapter of smart reading.

In recent years, a wide array of generative AI tools has rapidly emerged, dramatically accelerating how people access, analyze, and understand information. However, alongside these advancements come new challenges: difficulty discerning truth from falsehood, algorithmic bias, digital ethics, and personal data protection. In response, schools at all levels charged with cultivating the nation's future leaders are actively embracing creativity and innovation. By integrating reading and teaching with information and media literacy, alongside various emerging digital technologies, educators are encouraging students to effectively use digital tools to search for information, while also fostering critical thinking and deep learning skills. Through this process, students are inspired to remain curious, ask questions, and explore the world with a more informed and reflective mindset.

From Knowledge Giver to Learning Coach: Redefining the Role of Educators

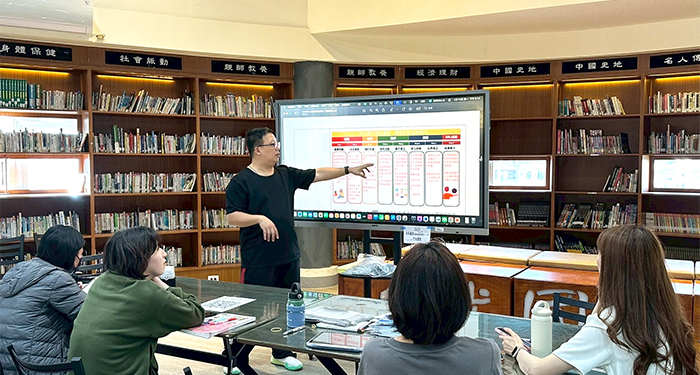

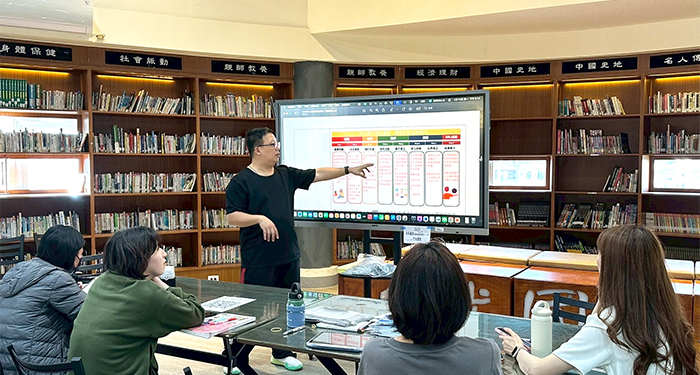

Amid the rapid rise of generative AI, Lai He Long, an information technology teacher at Taipei Municipal Zhongzheng Senior High School, has chosen to integrate AI into his classroom, redefining the role of educators from traditional “knowledge transmitters” to “learning coaches” and “strategic designers.” His focus is on nurturing students' information literacy and self-directed learning skills.

“The internet is like an ocean,” he explains. “If students are thrown into it without first learning how to swim in a pool, they’ll only drown.” This analogy highlights one of modern education’s core challenges: in an overwhelming flood of information, students need guidance—not passive instruction.

Starting with curriculum design, Lai He Long systematically guides students in using AI tools. For example, in a senior year course focused on college admissions, he asks students to formulate questions related to the academic programs they wish to apply to. They then use platforms such as ChatGPT, Perplexity, and Claude to conduct their searches and compare the responses. Through this process, students develop their information evaluation and question framing skills. “Students may not have known how to ask the right questions in the past,” Lai He Long explains. “But through this kind of learning experience, they can turn vague curiosity into concrete learning strategies.”

In addition, Lai He Long incorporates AI into interdisciplinary learning. In the Theory of Knowledge (TOK) course under the International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme (IBDP), he has students conduct “virtual interviews” with AI, asking it to impersonate artists such as Kusama Yayoi or Pablo Picasso. Students formulate questions, engage in simulated interviews, and transform their findings into classroom presentations. This is followed by an actual visit to a Kusama Yayoi exhibition, enriching the learning experience with real world depth. Through this process, students not only learn how to use AI tools but also begin to critically reflect: Is the information provided by AI reliable? Could there be biases behind it? This approach deepens their information literacy and strengthens their media literacy.

Lai He Long has also taken note of both the potential and challenges libraries faced in the AI era. At the “2025 Forum on Information Literacy in the Era of Smart Libraries” held by the National Library of Public Information, he delivered a talk titled “Smart Libraries x Digital Learning: Innovative Practices in Information Literacy Education.” He argued that if libraries become more intelligent and better integrated into teaching workflows aligned precisely with educational themes—they can evolve into extended spaces for information search and knowledge exploration. He envisions smart libraries becoming valuable learning companions for students.

“AI literacy isn’t just about knowing how to use tools—it’s about knowing how to interpret, question, compare, and synthesize information,” Lai He Long emphasized. The value of teachers, he insists, lies not in delivering the “right answers,” but in designing learning experiences that stimulate thinking and help students grow intellectually—a role that remains indispensable in the AI age.

Riding the AI Wave Libraries Transform into Learning Companions

Living in an era where AI powered information tools are rapidly transforming every field, Pan Wei Li, Director of the Library at Taipei Municipal Jianguo High School, has chosen to embrace change and actively explore how AI can be applied in educational settings. He recalls his first encounter with ChatGPT: “I initially thought it could only answer basic questions, but I was shocked to find that it could quickly generate a working web-based lottery program for the Taipei Mandarin Language Competition, and it functioned flawlessly." This experience left a strong impression and led him to reconsider the roles of both libraries and educators in this new technological landscape.

As both a library director and an information technology teacher, Pan Wei Li has gone beyond simply introducing generative AI into library operations such as automating grade notifications, designing an attendance system, and creating a book fair raffle program to significantly boost administrative efficiency. He has also integrated AI into his personal self-directed learning. Each day, he asks ChatGPT to explain classical texts such as the Analects, the Tao Te Ching, and Meditations, and has revisited complex literary works he once found difficult, including Dream of the Red Chamber, War and Peace, and The Three Musketeers: Twenty Years After. With AI offering contextual explanations and multi-perspective analyses, his reading has become richer and more nuanced. He describes AI as a “personal learning advisor that’s always by your side,” helping him maintain both a steady learning rhythm and depth of reflection during today’s information overload.

However, Pan Wei Li is also keenly aware of the myth of AI's so called "omnipotence." While generative AI can provide instant answers, overreliance without the ability to ask meaningful questions or critically evaluate responses may dull students' thinking skills. “The core of learning is agency,” Pan Wei Li stresses. “It’s not about passively receiving answers, but about knowing how to question, doubt, and make informed choices.” To that end, he has implemented a "Three No’s Policy" in promoting generative AI use at school: Don’t upload personal data, don’t blindly trust AI, don’t ask only once. These guidelines encourage students to ask follow-up questions and compare results, helping them strengthen their critical evaluation skills in the age of AI.

In Pan Wei Li’s eyes, the library is no longer merely a quiet corner where knowledge waits passively—it has become a “running companion” for students. It offers a tranquil, heartbeat like steady space that helps students reconnect with their learning rhythm, understand their own learning styles, and navigate the overwhelming flow of information to build a personalized learning map.

He firmly believes that in an era of widespread AI, the true value of humanity lies in our ability to choose, discern, and think critically. And it is precisely in these areas that libraries and educators can offer the most vital support to the next generation.

From Lesson Planning to Reading Making AI a Learning Ally for Teachers and Students

Chen Nai Cheng, a Chinese language teacher at Zhu Guang Junior High School and a longtime member of the Hsinchu City Digital Counseling Team, has spent over a decade advancing digital teaching and integrating information technology into the classroom. He believes that the emergence of AI has not only transformed how teachers prepare lessons but also infused teaching with greater flexibility and creative potential.

“In the past, designing three different levels of worksheets nearly drove teachers to exhaustion,” he remarked. “But now, with AI’s assistance, lesson preparation is not only more time efficient—it also allows us to focus more on guiding and interacting with students.”

From the early days of supporting the “Mobile Learning” policy to the current “Digital Learning Enhancement Program for Primary and Secondary Schools,” Chen Nai Cheng has consistently embraced innovation in education. He has recorded instructional videos, adopted interactive digital platforms for flipped learning, and now leverages generative AI for lesson planning and differentiated instruction—witnessing firsthand the transformation digital technology has brought to the classroom.

In response to concerns that AI may reduce students’ willingness to think independently, Chen Nai Cheng emphasizes that the key lies in how teachers integrate AI into their teaching strategies. He applies a “Four Learning” model: Self-learning by students, peer learning within groups, intergroup Learning, through collaboration, guided learning led by teachers. This approach focuses on designing purposeful learning tasks and guiding students to use tools effectively, cultivating their ability to search for and transform information.

“Those who know how to use AI won’t be replaced by it,” Chen Nai Cheng asserts. He views AI as an assistant, not a replacement, and believes that a teacher’s vision and skill ultimately shape the height of a student’s future.

This perspective also extends to reading promotion. Chen Nai Cheng points out that different students thrive with different learning methods, and reading is no longer confined to traditional print books. E-books, digital platforms, AI powered read aloud tools, and generative search engines have all become viable channels for accessing knowledge and cultivating comprehension. He shared a personal experience: originally uninterested in Dream of the Red Chamber, his perception changed completely after listening to the audiobook version of Jiang Xun's Youth Edition of Dream of the Red Chamber. Through that experience, he came to realize that “voice” can also spark passion for reading and learning.

Currently, Zhu Guang Junior High School continues to cultivate a strong reading culture through activities such as morning reading sessions, shared reading, book exchanges, and curated themed book exhibitions. The school has also developed flexible courses like "Self-Leadership", guiding students to develop self-awareness, planning skills, and autonomous learning abilities through reading. The recently renovated school library, which received recognition through the Reading Rock Award, has become a diverse, welcoming space where students can read comfortably and explore freely.

Chen Nai Cheng firmly believes: “In an era of rapidly evolving knowledge, what children need isn’t the standard answer, but the ability to embrace change and create new knowledge.”

Awakening Perception Through Visual Media: Encouraging Children to Speak Up with Confidence

At Pei Cheng Elementary School in Luodong Township, Yilan County, teacher Lee Yi Lun, who has long been committed to media literacy and visual education, guides students in observing the world through the lens and learning to express their perspectives through images and sound.

“Our goal isn’t to train journalists or filmmakers,” Lee Yi Lun says. “It’s to plant a seed in children’s hearts—a seed that makes them care about the world.” He believes that visual storytelling is more than a technical skill—it’s a process of cultivating observation, expression, and critical thinking.

In the summer of 2015, Lee Yi Lun led five student volunteers in creating the documentary, Fields. Full (田.滿), which captured the transformation of farmland across the Lan Yang Plain. Through aerial footage, the students were struck by how quickly farmland was disappearing. This discovery sparked deeper discussions on urbanization and land use, prompting them to design interview questions and take the initiative to speak with landowners and experts.

“In these interactions, they developed the courage to communicate with strangers and share their own ideas,” Lee Yi Lun recalls. “At the same time, the documentary making process opened their eyes to issues in their own hometown.” For Lee Yi Lun, visual storytelling became a gateway to civic engagement, guiding students beyond their textbooks and into the realm of real-world concerns.

Beyond regular classroom instruction, Pei Cheng Elementary School also hosts an annual graduation film festival to showcase student learning outcomes. Sixth-grade students present their self-produced documentary shorts, screened publicly in front of parents and classmates. Even when the pandemic necessitated a shift to online screenings, students’ passion for creation remained undiminished. Their works explored a wide range of topics, including water resources, air pollution, misinformation, and local culture—using hands on filmmaking to deepen their understanding of public issues and social responsibility.

Despite challenges in curriculum planning and limited teaching manpower, Lee Yi Lun remains committed to the value of visual education and media literacy, emphasizing that a teacher’s passion and teamwork are key drivers of success.

He encourages schools to flexibly design courses based on their own resources and conditions, without being constrained by high technical requirements. “Teachers don’t have to guide students through making full documentaries—drawing, reading, conducting interviews, or even basic video editing on a tablet can all be part of media literacy education,” he explains. The true focus, Lee emphasizes, is not the format but the mindset—nurturing children's ability to observe the world, ask questions, and confidently express their views.

In an era of ever-evolving technology and overwhelming information, the ways we read, think, and learn have already moved beyond traditional boundaries. Whether through transformed classroom teaching, the redefined role of libraries, or the use of visual storytelling and diverse media, educators are collaboratively forging a new path—one that integrates technology with the cultivation of essential literacies.

From this foundation of reading, children are learning to ask questions, explore bravely, doubt thoughtfully, and seek answers with confidence. These will be the most precious abilities in the age of AI.